Years ago at a party with a bunch of other foreign policy wonks I noticed a guest sitting quietly and not saying anything. I found this unusual because wonks like to talk a lot and show everyone around how clever they are so I introduced myself and asked what he did. He was a colleague of the host's wife and worked as a microbiologist. We talked about the general conversation and he observed, "You guys go somewhere and talk to some people and think you know something. That's just not what I do. I do experiments, under careful conditions I need to eliminate guesswork and assumptions."

There is a great deal happening across the greater Middle East and the TerrorWonk honestly can't keep up. But my interlocutor had a profound point. I'm not sure how much anyone knows about anything. We hear a great deal of conventional wisdom bandied about on everything - the Muslim Brotherhood, Gaddhafi, Assad and Syrian politics - you name it.

Unfortunately, the ability to collect the kind of knowledge that “counts” to a hard scientist is very difficult. But, whenever some part of the world erupts, we seem to know very little about it. We don’t know how much al-Qaeda is in the Libyan rebellion. I doubt we know much about the internal dynamics of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, and if Syria falls apart we won’t have a clue who is running the show.

I

work on models and recognize the difficulty of predicting a true “Black Swan,” that is a game-changing event. The countries of the Middle East are all ripe for revolution, but it didn’t happen for decades so why now? This is probably not an answer that can be given definitively.

But what can policy-makers do to caught a bit less flat-footed, when it occurs?

(Also, do you have any idea how hard it is to find a picture online of an actual black swan and not Natalie Portman.)

Escaping the InboxMost of our government is run by the mail – that is people try to answer whatever is in their inbox. This is how it has to be, but it leaves little time for deep thinking. At the same time, our government consists of vast organizations that develop organizational cultures, huge bodies of pre-conceptions, SOPs, and worldviews. While most agencies have planning boards of some sort, they are usually staffed by people who have served in other capacities so they are still very much part of that culture so that their thinking is shaped by the inbox.

The NSC was initially established to “staff” the president but over time has become an operational body. It is very hard not to get sucked into operations – ie answering the mail.

The intelligence community is extremely skilled at meeting the needs of its customers – the President, the armed services etc. But its ability to think deeply on non-pressing problems is limited. They do establish very capable specialized teams to take on high-priority issues.

Could a new intelligence agency be established specifically to research and prepare for outliers? Sort a classified university? (I have to grant some interest in this issue since I’d love to work at such a place.) Academia does a pretty good job of this sort of thing, but they have limited access to classified information. But what if such a group could fuse the academic research on the Muslim Brotherhood with whatever the IC has collected (which is certain to be extensive) and issue monographs, in-depth articles, and policy briefs. These researchers could also have a license to talk to agency experts on their issues. This way, if needed there is a ready source of expertise and a library on the Muslim Brotherhood that could be accessed to at least provide policy-makers reliable information. If Egypt doesn’t go under there would be another report sitting on a shelf somewhere.

There are budget constraints (there always are) but intelligence analysis is actually cheap compared to launching satellites and the other sophisticated collection mechanisms that US possesses. The IC’s budget is tens of billions of dollars, a modest sum ($20 million) could support 100 researchers easily.

The real challenge would be to keep such a group from becoming operational. Soon enough an IC executive or a politician would see these capable researchers and set them onto a pressing need. At the same time, these capable researchers might get tired of generating reports that no one reads and try to get positions n the IC proper. Various mechanisms could be adopted. Projects could be assigned and approved by a board of outside academics and maybe a term-limit on careers (ten years say and then move on) could keep the institution from getting stale or the researchers from getting bored.

A built-in red team/Black Swan organization could be extremely useful when disaster strikes. There are a number of relatively unlikely possibilities that someone should be thinking deeply about such as a state collapse in Pakistan (or hell – China – is that truly inconceivable)? What if Saudi Arabia goes under or even if oil production there peaks?

Most of these outliers wouldn’t come to pass. And even the terrible things that did happen, probably wouldn’t take the shape of this unit’s reports. But, as the military says, “Plans are nothing, planning is everything.” We need the institutions for deep planning.

Back to BusinessThis blog has gotten philosophical lately, in part because to write intelligently one needs to take in a great deal of information and then have something worth saying about it. There is too much information, and I kinda have job that occasionally requires my attention.

But, I shall attempt to again provide grounded analysis and perspective on the, while trying to shed light, not heat on the discussion. I'll start next week.

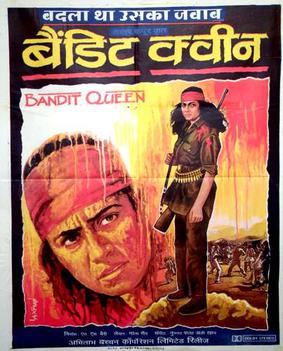

The Indian movie, The Bandit Queen tells a similar story based on the life of Phoolan Devi. There are a few differences, first that it is set in India, second that Phoolan turns to Muslim criminals for support against the Hindu higher castes, and that Mukhtar Mai has become an activist rather then a criminal. In the last point there is a small glimmer of hope. That a similar story is set among the Hindus of rural India highlights that this is not about Islam so much about tribalism.

The Indian movie, The Bandit Queen tells a similar story based on the life of Phoolan Devi. There are a few differences, first that it is set in India, second that Phoolan turns to Muslim criminals for support against the Hindu higher castes, and that Mukhtar Mai has become an activist rather then a criminal. In the last point there is a small glimmer of hope. That a similar story is set among the Hindus of rural India highlights that this is not about Islam so much about tribalism.